- The colonial era ? Arthur, 11

Summary

At the end of the dirt road, overlooking the Komo River and surrounded by forests, stands Donguila, the superb. In this village that the years have finally isolated, the road becoming a road and then a simple bumpy track, life has organized itself so that it does not feel abandoned. In 1878 the Catholic mission of Saint Paul de Donguila was founded, which gave birth to this small fishing village.

Here, the air is pure and time seems to be suspended, in a rhythm that we no longer know. The first impression is one of tranquility, a mixture of softness and harmony in the face of the grandiose spectacle offered by Mother Nature.

The mission today is at the time of rebirth. Over the years, the monks who lived there were buried, the girls' boarding school and the boys' boarding school had to be closed. But last year for the jubilee of the mission, and thanks to the efforts of the new priest, the boys' boarding school reopened its doors.

The old buildings of the mission have retained their former charm, even if the structure of the buildings is beginning to collapse like a tired old man. Only the church and the school buildings have been completely renovated. At the centre of the mission, three century-old mango trees, witnesses of Donguila's history, still sit in the middle of the courtyard.

Here live in boarding school 16 boys, from 6 to 15 years old, entrusted for the time of their education to Father Dimitri, guardian of the place and servant of Donguila. They are joined during the day at school by village children who join the ranks of the lightly crowded primary classes. There are less than 20 students per two-level class. Father Dimitri pays three quarters of the schooling of the most disadvantaged families in the village out of his own pocket.

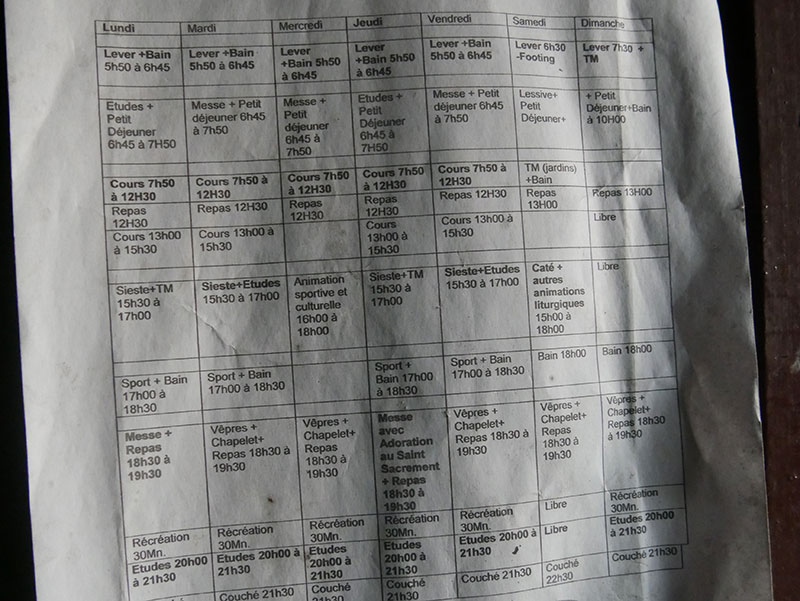

The children's day is scheduled to the rhythm of the church, and the sounds of bells. Masses,,, yard cleaning, school, meals, school, nap, spring water collection, vespers, meals, studies and finally rest. The days start at 5:50 and end at 21:30.

Father Dimitri, is dedicated to the mission and his village. He repairs the road after the heavy rains, transports the villagers to the city in his 4x4 when they are in need, fetches water from the well, goes to the market for food shopping, and finally organizes and animates the religious life of the mission. As a result, interns are often alone, left to their own devices for their studies, to lie down, or to fetch water.

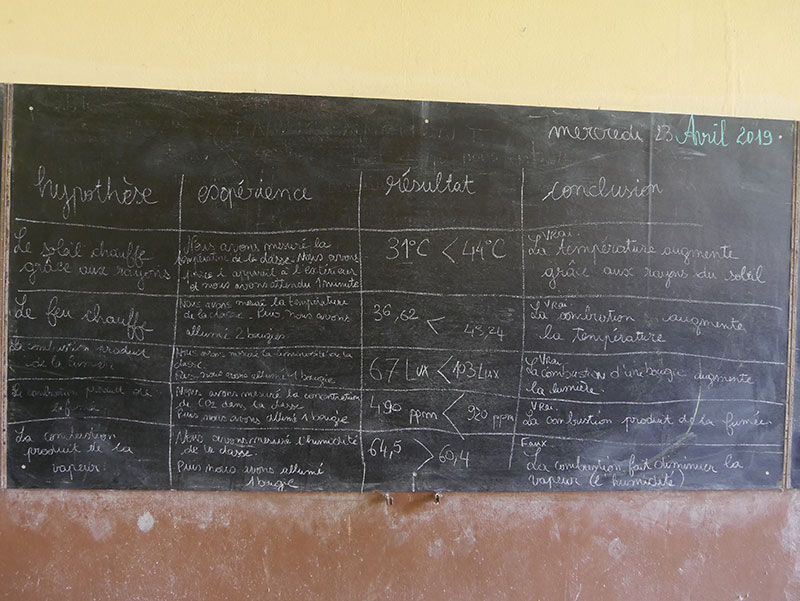

Far from the European child king, here children only have crowns of thorns to wear. Education is very strict, often violent with little room for empathy or comfort. In a desire for equality, respect for rules and others, the climate created by the fear of violence seems to accentuate it. Children complain of stomach pains, insomnia from being thirsty. Many have wounds that become infected and hurt them. Access to care is complicated so far from the city and the first doctors. In one experiment, we illustrated the pressure by pouring pressurized water into a basin. The children were outraged that water was wasted: "We are thirsty, Mr. Gordon".

Out of time and far from others, the children showed an immense curiosity about our coming that compensated for a lack of knowledge of the outside world. The forest is used primarily to cut wood. Biodiversity, holes in the ozone layer, recycling, oxygen, so many new concepts for these children.

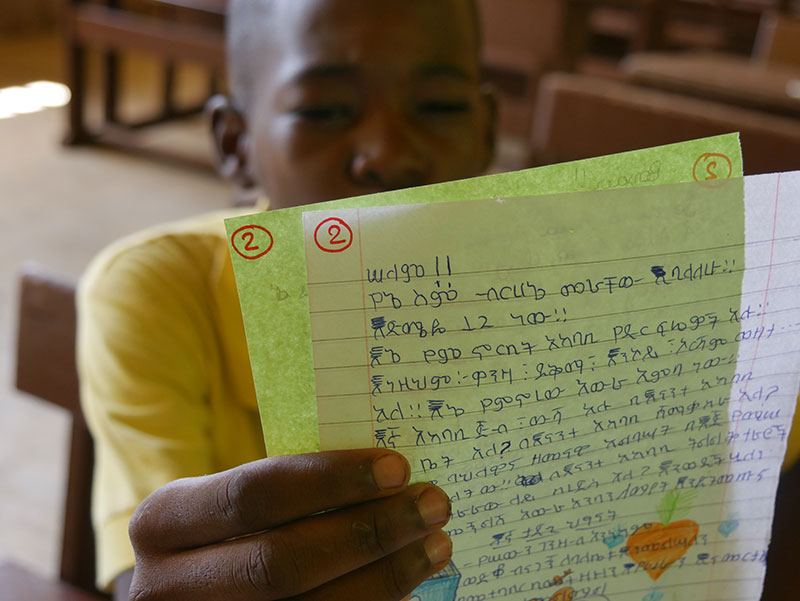

The reading of the Ethiopian letters addressed to them moved some, they felt happy that others had thought of them, and it "did them good".

We were surprised at the difficulty of group work for children who live together all the time. We found little mutual support and a lot of mockery between the children.

When they left, they wanted to give us flowers and hugged us. We asked them for two days to think about the environment in every gesture, in every action. In return, they simply asked us to think of them once they left.

Beyond the pedagogical experience and reflections on the environment, we experienced a human encounter that touched us deeply and raised questions.